Sparkling Wines from Sussex? Climate Change Swirls Wine Production

In the not too distant future, your favorite style of French wine may not come from its namesake region, or even from France at all. Climate change is altering growing conditions in wine-producing regions, and in coming decades it will change the wines produced in these regions — in some cases shifting northward the growth of grape varieties long associated with regions further south.

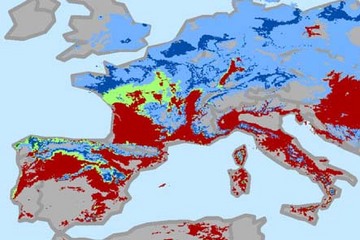

Climate change will produce winners and losers among wine-growing regions, and for every region it will result in changes to the alcohol, acid, sugar, tannins and color contained in each wine.

My research assistant Eric Hackert and I have analyzed climate change impacts on two dozen of the world’s major wine-producing regions across both the Old and New Worlds, providing snapshots of what conditions will be like at the middle and end of this century.

For example, several Champagne houses already are looking at land in Sussex and Kent in southern England as potential sites for new vineyards, because as climate warms the region, those areas are becoming more hospitable to quality grape growing. The soil type in the region (note the white cliffs of Dover) is similar to the chalky substrate of Champagne, and the cost of land is 30 times less than the premium to be paid per hectare in France.

In general, vineyards in higher latitudes, at higher altitudes or surrounded by ocean will benefit from climate change. These regions will experience more consistent growing seasons and a greater number of favorable growing days. They include the Rhine in Germany, the states of Oregon and Washington in the United States, and the Mendoza Province in Argentina and New Zealand.

Our research suggests Bordeaux and several other regions will suffer compressed growing seasons that yield unbalanced, low-acid wines that lack complexity. South Africa and South Australia likely will see declines in wine production due to severe droughts. Extreme events, such as heat waves that shut down photosynthesis and hail storms that can ruin a chateau’s annual production in a matter of minutes, will become more commonplace.

In both warm and cool regions, one result will be the same: wines will lose their traditional character. Taken to an extreme, a wine from the Left Bank of Bordeaux may move away from the classic aromas of cedar cigar box, blackcurrants and green pepper and more toward the full, rich, spicy-peppery profile of a Châteauneuf-du-Pape from the Southern Rhone.

Given that most grapevines produce fruit for 25 to 50 years, grape growers and wine makers must consider the long term when determining what to plant, where to plant and how to manage their vineyards. In the Old World, traditions may need to change with the times as appellation regulations restrict irrigation, wine-making practices and the grape varieties than can be planted.

This research is part of a broader effort at the University of Maryland (UMD), where my colleagues and I are working collaboratively to understand the Earth and its changing climate. As part of that work, the university has major research partnerships with federal agencies in Earth science, climate, and energy research. Our partnerships include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration-supported Cooperative Institute for Climate and Satellites; a long-standing cooperative agreement between UMD’s Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center and the NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center; and the Joint Global Change Research Institute, a partnership between UMD and the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

The impact of climate change on global viticulture is just one example of how the climate of the past is no longer prologue for the future. The warming of the planet will affect a number of areas of society and key sectors of the economy beyond agriculture, extending to human health, national security, hydropower and transportation, to name a few.

To aid individuals, institutions, industries and governments in effectively planning for and responding to climate change’s impacts, UMD’s Climate Information: Responding to User Needs (CIRUN) initiative is building diverse partnerships among climate scientists, behavioral and social scientists, engineers, agricultural scientists, public health and risk-management experts, and private- and public-sector decision makers.

Adaptations in grape growing and wine making represent only a few of the many adjustments the world will have to make as a result of the warming planet. However, these viticulture effects illustrate that climate change is not an abstract concept. Rather, in ways the world may not have appreciated, global warming will likely have an impact on the culture and way of life in many countries.