Rocky Mountain National Park Lightning Casualties July 2014

By: Scott Rudlosky

Two recent lightning fatalities in Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP) inform us of the tragic consequences that can accompany lightning. These terrible events were separated by one day and less than two miles. Sadly this marked the 10th and 11th lightning fatalities in RMNP since 1915 (first since 2000), and the 10th and 13th U.S. fatalities during 2014.

News stories have covered these events from many different angles (examples provided below), but none have discussed the lightning itself. Before we can understand the why, we must first understand the what. This article uses lightning and radar imagery to help better understand these events, and communicate lessons that may help to reduce future lightning casualties.

The geography of RMNP and the extraordinary access provided by roads and trails place park visitors at high levels of risk not typically experienced back home. During July through September, southerly winds from the North America Monsoon transport warm, moist air into the southwestern United States. As this tropical air encounters the Rocky Mountains, it is forced upwards, often producing intense thunderstorms. Daytime heating of elevated slopes can lead to sudden storm development with rapidly increasing lightning risk.

Thunderstorms often are difficult to see in mountainous regions, where topography blocks the visual cues that most people rely on to protect themselves from lightning. Lightning detection technologies can provide early warnings of approaching lightning, but use of this information remains limited, especially in regions with inadequate cell phone service. These tragic events remind us that thunder is the most direct detection method for lightning.

Following the July 11th event, when lightning killed one hiker and injured another seven, one of the survivors commented that “We were hearing claps of thunder everywhere, but there wasn’t any lightning.” (AP). They may not have seen lightning but thunder is merely the sound generated by lightning, so if there is thunder, there is lightning. During the hour immediately preceding the deadly strike, numerous intra-cloud lightning flashes were occurring less than 10 miles to the west. Unfortunately, from the Ute trail head, Sundance Mountain blocked the view of this storm to the northwest. Clouds are also nearer to the surface at this altitude, and the rocky terrain distorts the thunder, increasing the confusion and danger.

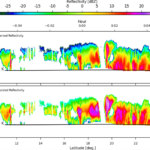

Radar imagery shows that this storm cell formed suddenly as outflow from an adjacent storm encountered Tombstone Ridge. The first cloud-to-ground flash (and obvious visual cue) occurred less than one mile away and only three minutes before the deadly strike, leaving too little time to make it safely back to the car. Figure 1 uses the WeatherBug Earth Networks Total Lightning Network (ENTLN) to show all of the lightning events in the vicinity and their distances from the incident location. Figure 2 zooms in to illustrate the lightning as observed by the National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN, Vaisala Inc.). Both networks detected intra-cloud portions of this flash, and both indicated that the flash had multiple ground strike points. Scientists have shown that mountainous terrain can increase the likelihood of multi-strike cloud-to-ground flashes.

The circumstances differed the following day (July 12th), when lightning struck the Rainbow Curve parking area, killing one and injuring three. Intermittent lightning flashes were occurring along a distant ridge (5-10 miles to the south) for 45 minutes preceding this event, suggesting that thunderstorms could be heard. There were no cloud-to-ground flashes within 5 miles of the deadly strike before it suddenly occurred (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). The storm that produced the fatal flash had formed a few miles north less than 30 minutes earlier. This deadly storm only became noticeable on radar near the same time it began producing intra-cloud lightning (5-10 min prior to the cloud-to-ground strike).

Both the ENTLN and NLDN detected intra-cloud portions of this deadly flash two miles east of the cloud-to-ground strike location (Figs. 3 and 4). This suggests that the flash traveled some distance outside of the cloud edge before striking ground (not a rare occurrence). The radar imagery suggests that the storm formed quickly and passed northeast of the incident location. Sadly, as it passed, it appears that a flash exited the side of the storm, traveling more than 2 miles before striking ground.

The exact reason why a lightning channel follows its particular path escapes even the densest lightning observation systems. Although these flashes may seem random and unpredictable, the signs of lightning (rain, clouds, distant thunder) are almost always present before it strikes. In many places, the first step to protecting yourself from lightning is noticing the growing cumulus towers, especially if storms are in the forecast. These tragic events in RMNP show that under certain circumstances, you can go from a small cloud to a lightning producing storm in under 30 minutes.

During the July 11th and 12th events, vehicles and restroom facilities were available nearby to provide relative safety (termed the front country), which is not the case throughout most of RMNP (the backcountry). Since no place in the backcountry is completely safe from lightning, the following pamphlet was produced to help educate hikers and backpackers. It instructs them to avoid the highest risk locations at the highest risk times, just like they do with other hazards like rockfalls and avalanches (Lightning Risk Mitigation in the Backcountry). This document is strongly recommended to anyone venturing into the backcountry during thunderstorm season.

The common attribute shared by t

hese recent deadly flashes is that they struck ground outside heavy rain and away from the most obvious threat. Education and awareness are the keys to protecting people and property from lightning. Be an advocate and speak up if conditions seem unsafe. You do not need to wait for an authority figure to seek safety. Remember, lightning makes thunder and “When Thunder Roars, Go Indoors!”

Colorado Lightning Mapping Array Animations

COLMA Animation (11 July 2014)

COLMA Animation (12 July 2014)

COLMA Visualization – Real-time and Archive

Links to External Media Reports