By: Brian Compere

Publisher: Council on the Environment

Published: June 3, 2013

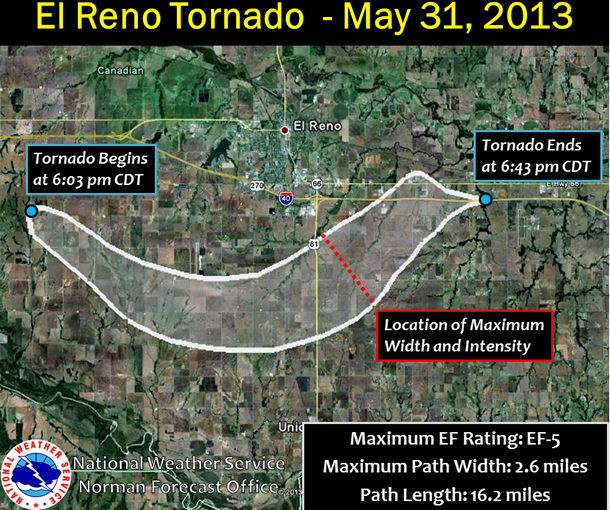

On May 20, a powerful tornado more than a mile wide killed 24 people as it tore through 17 miles outside Moore, Oklahoma. On Friday, an even stronger tornado – the widest ever recorded on Earth – killed 18 after touching down in Oklahoma City and its suburbs.

In light of this destruction, it may be surprising to learn that tornadoes have actually been occurring less often than they have in more than 20 years.

Scott Weaver, a research meteorologist for the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center, said although this particularly destructive string of tornadoes might raise concerns about tornadoes in the future, 2012 had the lowest number of recorded tornadoes than any year since 1989.

While the NWS had recorded 441 tornadoes this year as of Thursday, the annual trend of tornadoes in 2005 to 2011 through May 30 is 827, almost double the number of tornadoes that have occurred so far this year. In addition, Weaver said 2012 saw the fewest tornadoes since 1989.

If anything, the number of tornadoes touching down seems to be trending downwards.

However, Weaver said it isn’t possible to identify long-term trends and changes in tornado activity because the data record is unreliable. Tornadoes can touch down in isolated, rural areas and not be recorded; because of this, tornado data could be influenced by factors like population changes rather than by scientific meteorological trends.

“Had that tornado occurred over a bunch of farmland, you wouldn’t be hearing anything about it,” Weaver said. “And that’s the challenge here, is that when you have something like that happen, people are going to automatically go like, ‘oh boy, it must be global warming, or it must be this or that,’ and as it relates specifically to tornadoes, that is not necessarily true.”

Tornadoes like those that touched down on May 20 and on Friday with EF5 rankings – the highest ranking a tornado can receive – may seem large, but in the grand scheme of the climate, Weaver said, they are actually so insignificant that they are not included in climate models. This is a main reason why it is much more difficult to identify trends with tornadoes than with precipitation-based weather events such as hurricanes.

It is possible, however, to make general predictions about tornadoes by considering factors that lead to tornadoes: Scientists can use climate models to predict how these factors will change. For example, if the vertical wind shear – the change in wind direction and/or speed with height – is projected to decrease, tornadoes should be less likely to occur since it is a necessary factor.

The other main factor for the formation of tornadoes, Weaver said, is convective available potential energy (CAPE), a measure of atmosphere stability. Both factors are needed for tornadoes to occur.

Even looking at these two factors in climate models can’t predict the nature of tornadoes in the future very well, however, because CAPE is projected to increase, while vertical wind shear is projected to decrease. If they work against each other as expected in many climate models, it is unclear how tornadoes will be affected by what Weaver called a “tug of war” between the two factors.

Regardless of how tornadoes end up affecting the climate in the future, Elise Miller-Hooks, a civil and environmental engineering professor at the University of Maryland, believes it’s necessary for communities to prepare for severe weather events common to their areas – this includes tornadoes for states like Oklahoma.

“It’s important that every community have an emergency plan dealing with these things and that the citizenry be prepared for such events that are more typical – maybe not typical but that are concerns for that particular location,” she said.

Miller-Hooks, who researches emergency preparedness, response and recovery, among other topics, said she is researching the trade-off between preparedness and response to severe weather damage. If fewer resources are spent on preparation, she said, response will need to be much larger and more costly.

“Society needs to trade these things off; do they want to put their efforts into emergency preparedness that have low probability, but maybe its probability is increasing now? Or do they want to wait until it’s happened, take their chances and put more money into the response later?” she said.

In order to better prepare for weather-related emergencies like tornadoes, Miller-Hooks said general education and training can be very helpful in ensuring that fewer lives are lost to strong tornadoes or any other extreme weather event.

The string of tornadoes in the Oklahoma City area has led to public interest in legislation to make tornado shelters mandatory in all Oklahoma schools and day care centers. Two Change.org petitions advocating such a policy had a total of more than 24,000 signatures as of Monday.

Even if work isn’t done to improve infrastructure, Miller-Hooks said, education can be a less costly way for communities to better prepare themselves.

There is no doubt that the Oklahoma City area has experienced an unusual amount of tornado damage in the past couple weeks, but Weaver said it isn’t possible for climate scientists to be able to predict if strings of strong tornadoes like this one are going to become more common in the future.

Either way, though, it is clear to Weaver that these tornadoes were not out of the ordinary, and they simply had the unfortunate luck to land in a populated area. He said there’s no scientific reason for this.

“It’s a tricky subject when you’re talking about climate and tornados because from the climate perspective, this is not an active year. But try to tell somebody that who lives in Oklahoma,” Weaver said. “As far as we know, it’s simply just bad luck, random chance. There’s no real scientific reason why they’d be lining up in more populated areas at this time.”

Reprinted from Council on the Environment with permission. http://cone.umd.edu/index.php/news-events/328-okla-tornadoes-likely-due-to-random-chance.