By Jacob Bell

Heat waves are prolonged periods of high temperatures that can cause crop failure and human health problems ranging from dehydration to stroke. A new study, however, suggests that the agricultural community can play a role in mitigating such extreme weather. .

Depending on how they manage their fields, farmers can decrease local temperatures by nearly 2 degrees Celsius during heat waves, according to researchers at ETH Zurich, a science, technology, engineering and mathematics university in Switzerland.

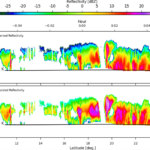

A six-year analysis by ETH Zurich researchers on a field in southern France found that local temperatures decreased when farmers left their fields untilled post-harvest since the light-colored crop residue increased albedo.

“The albedo is the fraction of the solar radiation reflected by the land surface,” said Dr. Edouard Davin, the first author of the study and a senior lecturer at the Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science. The study found that this increase was especially prominent during summer months and that no-till farming could serve as a useful instrument to combat heat waves.

“This is an important result because humans and ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to heat waves,” Davin said.

More than earthquakes, floods, hurricanes and tornados combined, heat waves are the deadliest form of severe weather, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. On average, nearly 700 people in the U.S. die each year due to extreme heat exposure.

Subsequently, if the current rate of climate change and greenhouse gas emissions continues unabated, the number of heat waves and the people they affect will grow both locally and regionally.

By 2050, researchers expect heat-related deaths to total between 3,000 and 5,000 nationwide, and temperatures in Maryland and the northeast are expected to increase an average of 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit to 10 degrees Fahrenheit, according to reports from the CDC and the 2014 National Climate Assessment.

But for regions with large agricultural industries, no-till farming offers a way for farmers to protect their crops and their communities from unbearable temperatures.

A 2011 federal report states that the Maryland agriculture industry utilizes 2.05 million acres or 32 percent of the state’s land. The industry is also the largest commercial trade in Maryland, with 13,000 farms and around 350,000 workers.

Despite the new ETH Zurich research, no-till farming presents obstacles that are keeping some from adopting the practice.

The Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) is a nonprofit organization that independently critiques agricultural production, handling and processing. Currently, there are no reliable chemicals endorsed by the OMRI that fight broad leaf weed or grass growth, according to Dr. Gerald Brust, an IPM Vegetable specialist at the University of Maryland’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. As a result, tilling serves as a primary form of organic herbicide.

Obstacles aside, no-till farming is gaining traction. In fact, Davin stated that many farmers already use no-till field management for its array of fiscal and environmental advantages, such as reduction in soil erosion, water loss and energy expenditures.

With his latest research, Davin added that farmers could put ‘dampening the effect of heat waves’ on no-till farming’s list of benefits.