A group of volunteers including ESSIC scientist Fernando Dos Santos are putting together an interactive map that tracks the spread of COVID-19 across Brazilian states and cities.

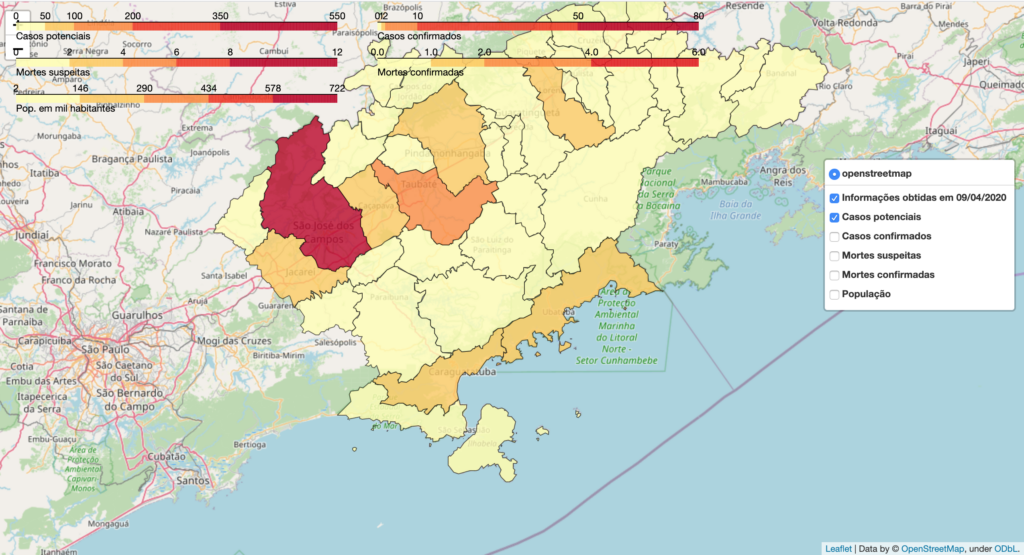

The project, titled MapaVale, uses data collected from official city webpages and through private conversations with city officials to record suspected and confirmed cases and deaths that can be attributed to COVID-19. The team has already recorded data along the southeast coast of Brazil.

“We are focusing on having a reliable database that can be used by the scientific community but also to communicate and inform the general public, as well as point out flaws and communication gaps along with the time series data,” says Dos Santos, an ESSIC visiting assistant research scientist.

One of the most crucial tasks that MapaVale has taken on is standardizing the data they collect from public officials and city websites. In Brazil, each state is individually reporting data using their own standards and measurements. Coordination between cities, states, and the federal government are nonexistent. Important variables such as age, sex, hospitalization of patients, and spatial information are often outdated or not documented at all, according to Dr. Ana Araujo, a geographer working at Laboratory for Investigation of Socio-Environmental Systems – INPE/Brazil and teacher in São Sebastião.

“We also have noticed that the terminology surrounding potential cases varies from city to city in Brazil. Often, the authorities are not using the phrase ‘suspected’ case as a unique definition per se. Instead, those that are suspected of having COVID-19 are often segregated into different categories such as ‘self-monitoring at home,’ ‘admitted to a hospital,’ or ‘waiting for a test result,’ and it is not clear if they are part of the same group,” states Dos Santos.

MapaVale makes this data easier to communicate by aggregating these segregated lists into a single section: “potential cases”. Regarding suspected deaths, the MapaVale team reports what is being communicated by municipalities, but they have noticed that official numbers tend to be reported inaccurately. Berenice Aparecida, a group member that works as a geography teacher in Lorena, notes that COVID-19 deaths tend to be falsely labeled as suspected deaths due to a lack of lab tests carried out in a timely manner.

“We know that the numbers are being drastically underreported in some places in the world, mostly due to limitations with COVID-19 testing and also due to the lack of information and standardized procedures. This problem leads us to believe that there is a false perception of the danger that the disease poses at a regional level.”

Fernando Dos Santos, 2020.

Dos Santos, who also works on NASA Pandora Project at Goddard Space Flight Center, joined the project when he noticed the difficulty of data interpretation by the public in certain countries like Brazil. The MapaVale team encompasses young scientists and local people like him with broad expertise and who are acting in different fields and institutions. MapaVale is not currently affiliated with or funded by any organization; all those involved are volunteers.

“We hope that MapaVale can heighten public awareness of risk as well as address access inequality to opportunities and response capacity for each municipality,” says Anna Leite, a participant in the project who is also a geographer and teacher in Taubaté, a city located in the study area.

Using spatial analysis and statistics, MapaVale can uncover new insights and information about disease spread and even reveal critical locations. This could help decision-makers allocate the limited number of civil servants to the most at-risk regions and predict future spread.

The team has already identified at least two potential clusters in the Paraíba Valley region. The first is the city of São José dos Campos, an industry and research hub located between São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, two of the most active production and consumption metropolitan regions in Brazil. The second is the cities of Caraguatatuba and São Sebastião, coastal towns where the residents of São Paulo and São José dos Campos often go on summer holidays and prolonged weekends.

“Another important aspect is the public perception of the risk that COVID-19 poses,” says Dos Santos, “In a country with high levels of economic and educational inequality like Brazil, along with political interests and the mass production of fake news, it is imperative to alert the people of the risks of this new pandemic disease.”

Currently, the team is working to incorporate air pollution impact and vulnerability information into the map, such as a region’s level of poverty, aging population, and the number of smokers. The team hopes that this data can be correlated with the spatial evolution of the COVID-19 cases to see which variables have the most significant impact on the spread. The team is also working towards displaying the impact of no-quarantine politics and the interconnection between cities and how these factors might affect disease evolution.

“Direct action in the local community can bring a sense of citizenship and participation that is highly beneficial to society, especially for those who are somehow marginalized,” says Dos Santos, “The legacy of this project lies in the community’s engagement in the construction of scientific knowledge.”

For more information about MapaVale, and to see the interactive map, click here.