The influx of salt in streams and rivers is an ‘existential threat,’ according to a research team led by a UMD geologist.

The planet’s demand for salt comes at a cost to the environment and human health, according to a new scientific review led by University of Maryland Geology Professor Sujay Kaushal. Published in the journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, the paper revealed that human activities are making Earth’s air, soil and freshwater saltier, which could pose an “existential threat” if current trends continue.

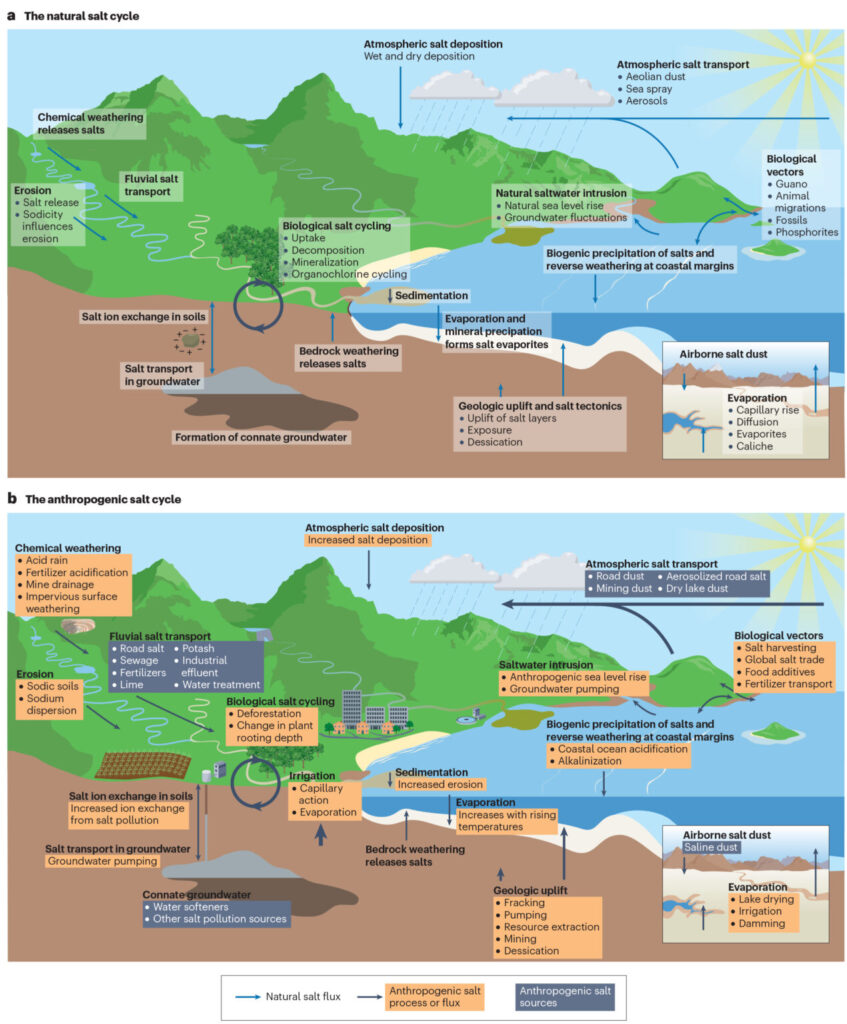

Geologic and hydrologic processes bring salts to Earth’s surface over time, but human activities such as mining and land development are rapidly accelerating this natural “salt cycle.” Agriculture, construction, water and road treatment, and other industrial activities can also intensify salinization, which harms biodiversity and makes drinking water unsafe in extreme cases.

“If you think of the planet as a living organism, when you accumulate so much salt it could affect the functioning of vital organs or ecosystems,” said Kaushal, who holds a joint appointment in UMD’s Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center. “Removing salt from water is energy intensive and expensive, and the brine byproduct you end up with is saltier than ocean water and can’t be easily disposed of.”

Kaushal and his co-authors described these disturbances as an “anthropogenic salt cycle,” establishing for the first time that humans affect the concentration and cycling of salt on a global, interconnected scale.

“Twenty years ago, all we had were case studies. We could say surface waters were salty here in New York or in Baltimore’s drinking water supply,” said study co-author Gene Likens, an ecologist at the University of Connecticut and the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. “We now show that it’s a cycle—from the deep Earth to the atmosphere—that’s been significantly perturbed by human activities.”

The new study considered a variety of salt ions that are found underground and in surface water. Salts are compounds with positively charged cations and negatively charged anions, with some of the most abundant ones being calcium, magnesium, potassium and sulfate ions.

“When people think of salt, they tend to think of sodium chloride, but our work over the years has shown that we’ve disturbed other types of salts, including ones related to limestone, gypsum and calcium sulfate,” Kaushal said.

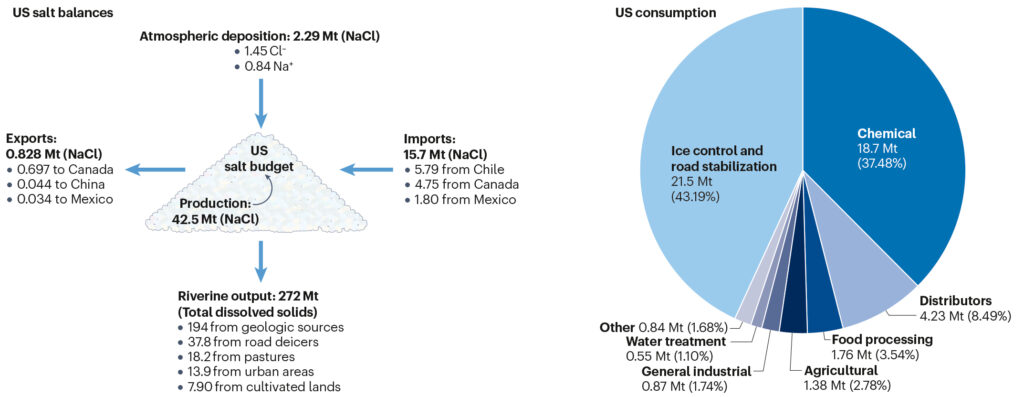

When dislodged in higher doses, these ions can cause environmental problems. Kaushal and his co-authors showed that human-caused salinization affected approximately 2.5 billion acres of soil around the world—an area about the size of the United States. Salt ions also increased in streams and rivers over the last 50 years, coinciding with an increase in the global use and production of salts.

Salt has even infiltrated the air. In some regions, lakes are drying up and sending plumes of saline dust into the atmosphere. In areas that experience snow, road salts can become aerosolized, creating sodium and chloride particulate matter.

Salinization is also associated with “cascading” effects. For example, saline dust can accelerate the melting of snow and harm communities—particularly in the western United States—that rely on snow for their water supply. Because of their structure, salt ions can bind to contaminants in soils and sediments, forming “chemical cocktails” that circulate in the environment and have detrimental effects.

“Salt has a small ionic radius and can wedge itself between soil particles very easily,” Kaushal said. “In fact, that’s how road salts prevent ice crystals from forming.”

Road salts have an outsized impact in the U.S., which churns out 44 billion pounds of the deicing agent each year. Road salts represented 44% of U.S. salt consumption between 2013 and 2017, and they account for 13.9% of the total dissolved solids that enter streams. This can cause a “substantial” concentration of salt in watersheds, according to Kaushal and his co-authors.

To prevent U.S. waterways from being inundated with salt in the coming years, Kaushal recommended policies that limit road salts or encourage alternatives. Washington, D.C., and several other U.S. cities have started treating frigid roads with beet juice, which has the same effect but contains significantly less salt.

Kaushal said it is becoming increasingly important to weigh the short- and long-term risks of road salts, which play an important role in public safety but can also diminish water quality.

“There’s the short-term risk of injury, which is serious and something we certainly need to think about, but there’s also the long-term risk of health issues associated with too much salt in our water,” Kaushal said. “It’s about finding the right balance.”

The study’s authors also called for the creation of a “planetary boundary for safe and sustainable salt use” in much the same way that carbon dioxide levels are associated with a planetary boundary to limit climate change. Kaushal said that while it’s theoretically possible to regulate and control salt levels, it comes with unique challenges.

“This is a very complex issue because salt is not considered a primary drinking water contaminant in the U.S., so to regulate it would be a big undertaking,” Kaushal said. “But do I think it’s a substance that is increasing in the environment to harmful levels? Yes.”

###

In addition to Kaushal, other UMD-affiliated co-authors included Carly Maas (M.S. ’22, geology), geology master’s student Joseph Malin, Jenna Reimer (B.S. ’19, geology), Ruth Shatkay (B.S. ’19 architecture; M.S. ’21, environmental science and technology), geology Ph.D. student Sydney Shelton, and Alexis Yaculak (B.S. ’21, geology).

Their paper, “The Anthropogenic Salt Cycle,” was published in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (Award Nos. GCR 2021089 and 2021015), Maryland Sea Grant (Award No. SA75281870W) and the Washington Metropolitan Council of Governments (Contract No. 21-001). This article does not necessarily reflect the views of these organizations.