Wildfires are a growing threat to the global population. As temperatures rise, rainfall patterns shift, and the landscape is modified, fires are becoming more difficult to predict. Satellites often provide fire managers and researchers with the first line of information, delivering data that supports monitoring and decision-making.

University of Maryland Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center (ESSIC) scientist Shane Coffield has discovered a new method to extract significantly more information from existing satellite-based fire detection systems. By combining satellite imagery algorithms with deeper fire-behavior knowledge, this approach offers a more complete picture of wildfire activity.

Scientists rely on a sensor called the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) onboard three different satellites looking at the Earth. VIIRS is crucial for fire detection, especially in remote parts of the world where satellite data may be the first — or only — source of information.

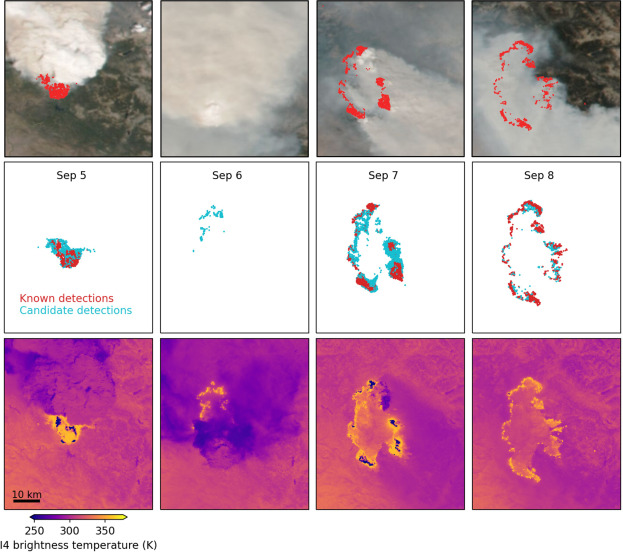

However, because VIIRS is observing the Earth from a distance, obstructions near the surface can limit its observations. Cloud, smoke cover, and even tree canopies can block VIIRS from seeing fires. Coffield observed this while reviewing VIIRS imagery of the Creek Fire, a wildfire that burned hundreds of thousands of acres of land across central California in late 2020. He noticed a massive pyrocumulonimbus cloud – a storm cloud generated by the convection from fire – visible in the imagery but blocking VIIRS from flagging the area as a fire.

“Despite having no fire detections on that afternoon, I was still able to see much of the fire in the raw imagery,” said Coffield, Assistant Research Scientist at ESSIC and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, “That clued me in that there was clearly more information we could be pulling out and using during these periods where scientists, forecasters, and fire managers are otherwise flying blind.”

VIIRS captures images at a coarse resolution – each 375m x 375m location is represented by one pixel in the satellite imagery. Fire detection algorithms scan each pixel and flag hot spots of potential fires. These algorithms are intentionally conservative to prevent false alarms. Pixels that partially meet fire criteria are labeled as candidate fires, but are not delivered to scientists and fire managers as part of the standard set of fire detections.

Coffield discovered that candidate fire pixels can reveal additional fire activity, particularly useful during periods with dense smoke, cloud cover, or low-intensity fires.

“At least in the case of tracking ongoing wildfires, it can be helpful to pull in this additional “candidate” fire information for more detail about the fires, especially when it’s really cloudy or smoky. For example, existing fire detection approaches could be adjusted to be more sensitive when we already know a wildfire is occurring, or to simply provide this candidate fire information in a more easily accessible format. This includes near real-time fire detection and near real-time fire tracking such as that provided by the Fire Event Data Suite,” said Coffield.

Coffield’s team revised VIIRS data to identify fire activity concealed by smoke, clouds, or vegetation. They discovered that using these candidate pixels could improve smoke models and air quality forecasts, particularly during extreme fires. In the case of the Creek Fire, having this information accessible in near real-time would have improved smoke forecasts, which previously lacked fire activity information on multiple days with high intensity burning.

“This will help us better understand fires during smoky conditions, fire smoldering, and low intensity but high impact burning like prescribed fires and burning in the tropics,” said Tempest McCabe, ESSIC scientist and second author on the paper.

This method could also improve fire detection for crew safety and support further advancements in regions where data are limited. The Wildfire Tracking Lab plans to integrate these findings into algorithms to better track obscured fires and identify remaining hot spots, especially in tropical regions.

The team believes that new satellite missions are needed, especially for observing fires at higher resolution and peak burning times in the afternoon. But this research shows how we can also make progress to push on improving the information we extract from existing sensors.

“Normally, the community has to wait for slow-to-deploy new satellite missions for more detections,” said McCabe, “[This work] has shown us the additional value in what was in front of us the whole time.”